This article was originally published on Stanford Social Innovation Review.

Authors: Mélanie Marcel, Leena Al-Olaimy and One Young World Ambassador Tariq Al-Olaimy

This year’s World Environment Day theme, “Connecting People to Nature,” implores us to get outdoors and appreciate Planet Earth’s beauty and importance. As environmentalists, we try to protect nature. Biomimicry inspires us to learn from nature. But overall, we are not consciously partnering with nature to create a better world.

Indigenous communities have long partnered with the natural world to achieve cost-effective, resource-efficient, sustainable solutions that mutually serve human and ecological needs. One example of such a symbiotic relationship is believed to be thousands of years old and features honeyguide birds, which are famous for leading people to honey. The birds—neither domesticated nor coerced—lead African hunters to hidden beehives in the forests. After the hunters harvest the honey, the birds enjoy a banquet of discarded beeswax.

As we look to the private sector to bridge an annual investment gap of $2.5 trillion to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by 2030, we may be overlooking our most promising—and arguably only—solution for survival and regenerative development: nature itself.

Private sector engagement presents part of the solution, but let’s be honest: Given humans’ track record in accelerating our own extinction, short-term economy typically outranks long-term ecology.

The recent withdrawal of the United States from the Paris climate accord highlights these failures and adds an additional $2 billion gap to the Green Climate Fund, which provides climate finance investment in low-emission, climate-resilient development.

Meanwhile, conservationists struggle to promote natural infrastructure as economically and ecologically lucrative, even though they are invested in finding ways to use financial incentives to preserve nature.

In reality though, nature doesn’t need our “protection,” and it’s worth asking: Has our fervor for human-centered design eclipsed our ability to recognize opportunities for “non-human centered” solutions that integrate nature as an innovation partner in sustainable development?

A New Approach: Public-Planet Partnerships (PPPs)

First of all, by “public,” we mean businesses, governments, social innovators, and scientists—essentially, the human world.

By “planet,” we mean leveraging the wisdom of more than 9 million species over 3.8 billion years of research and development, and priceless patents and algorithms. Plus, more than $100 trillion in free ecosystem services provided through natural capital—the world's stocks of natural assets, including soil, air, water, and all living things. The cost-equivalent of humans replicating these is incomparable.

And by “partnership,” we mean mutually beneficial, win-win collaborations between public and planet. There are many examples of the public attempting to partner with the planet across various sectors: partnering with fungi to fight global hunger by creating climate adaptive crops, partnering with pigeons to monitor air pollution, and partnering with frogs to collect data on water health indicators.

Two examples related to water—in recognition of this month’s landmark UN Ocean Conference—are The Ocean Cleanup and New York City Watershed Agreement.

By 2050 there will be more plastic than fish in the sea. Using conventional methods to clean the ocean—vessels and nets—would take thousands of years and tens of billions of dollars to achieve. The Ocean Cleanup is a passive waste collection system partnering with the ocean’s natural currents, with the potential to remove 50 percent of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch in 5 years, at a fraction of the cost.

Meanwhile, for 20 years the New York City Watershed Agreement has facilitated the natural percolation of water through partnering with microorganisms in the soil of the Catskills at a cost of around $100 million per year, versus $8-10 billion to build a water filtration plant. In addition to providing the “champagne” of drinking water for 9.5 million New Yorkers, watershed management is beneficial to the eco-system, because it minimizes soil erosion and nutrient loss, reduces flooding, and even manages problematic invasive species.

Acknowledging the need for greater research to quantify all the economic, environmental, and social benefits of PPPs relative to traditional solutions, we are cautiously optimistic that, united under a common framework, isolated case studies such as these could provide us with a new framework for achieving the SDGs.

Building PPPs

The PPP framework was developed in partnership between 3BL Associates and SoScience to help create new solutions that solve specific challenges linked to the SDGs or to improve existing solutions within an organization. Given the limitations of public-private partnerships—in that they don’t consider the planet as a stakeholder or collaborator—we believed there was a need for eco-inclusive “Public-Planet Partnerships,” and launched the first pilot PPP workshops during the UN COP 22 Climate Conference in Morocco, with the support of Ashoka and the Robert Bosch Stiftung.

Comprised of tools, case studies, and links to technical resources, the framework starts with inviting innovators to engage in an ethos dialogue, with the goal of understanding the ethics and values required to guide the rest of the process. This is the basic understanding that we are looking for mutually beneficial, win-win collaborations, rather than exploiting nature’s resources for the primary purpose of human gain. Popular circular economy initiatives embed other species into solutions, but in certain cases, they offer little mutual value to our planetary partners and don’t fully harness their eco-system potential. The Cardboard to Caviar initiative is one example. It focuses on feeding worms composted waste, which are in turn fed to sturgeon fish, which are later killed to harvest caviar, but there is no regenerative or net positive benefit to nature.

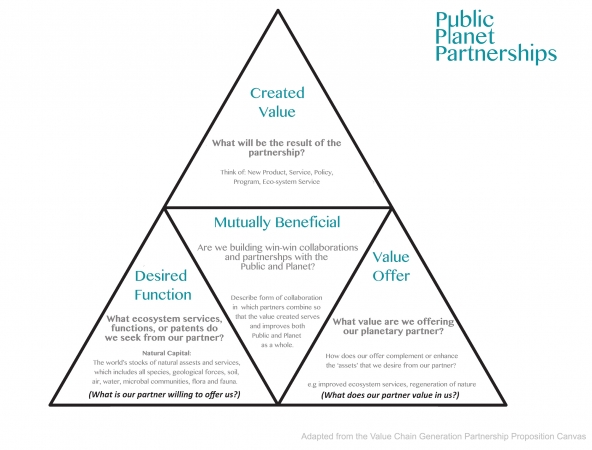

Just like a traditional public-private partnership, the framework provides the tools to map out stakeholders, as well as the environment, resources, and potential innovation partners in nature. Tools like the Public-Planet Partnership canvas offer a guide to choosing the right planetary partners, identifying the desired functions we seek from our partners, and, more importantly, determining the value we offer our planetary partners in terms of ecosystem services and regeneration.

The Public-Planet Partnerships Canvas acts as a guide in selecting the right planetary partner and finding a mutually beneficial collaboration between the public and planet.

Using multiple tools to assess the effectiveness of a solution, the framework revolves around a fundamental question: Are we building win-win collaborations for the public and the planet?

“En-clusivity”

One response from the international community to the withdrawal of the United States from the Paris accord has been to “Make the Planet Great Again.”

Within the context of PPP, climate justice is not only an inter-generational issue, but also an inter-species issue, and it requires that we be environmentally inclusive of the planet (“en-clusive”), as was the case when the government of New Zealand granted the Whanganui River personhood rights.

The PPP concept propagates the idea that human development can heal and regenerate Earth. This recognition comes from the understanding that humans have always developed the places they’ve inhabited and that many cultures throughout history have had symbiotic partnerships with the land. The goal of PPPs is to rekindle this wisdom, integrate it into the evolutionary insights of modern science, and apply it to social innovation and development.

Tariq Al-Olaimy is cofounder of 3BL Associates, a people+planet strategy consultancy and think-do-tank advancing progress on inter-connected sustainable development issues like climate change, peace, and health. He is a biomimicry specialist, an Ubuntu Peer Peace Coach, and a World Economic Forum Global Shaper. He also serves as a co-chair of UNESCO's Global Action Programme on Education for Sustainable Development Network.